Sociology professor Christian Schmid will retire this year. In an interview with Andres Herzog, he looks back on his time at the ETH Studio Basel, which sparked discussions with the book “Switzerland: An Urban Portrait” and whose publications will be freely available online as Open Access from May.

Sociology has only existed in the Department of Architecture since the 1960s. Why is the discipline important for architecture?

It’s hard for me to imagine an architecture school without sociology. Of course, construction and building services are required. But we don’t just build for the gallery and for glossy magazines, we build for practice. And that means, first and foremost, for the people who use and live in these buildings. Building always takes place in a social, political and economic context. There is hardly any other profession that works with such different social groups: from building owners to planning officials to craftsmen. Architects are generalists. But it also requires specialized knowledge from various other disciplines, such as sociology and geography.

Do sociological aspects play a more important role in planning today than before?

In any case. You can already see this in the architectural competitions, which increasingly require a social space analysis. Building used to be more standardized, architects had to follow the zoning plans. Today we build in many different situations. Planning has become more complex, there are many more exceptions that are dealt with, for example with specific planning regulations. And this is where sociology becomes indispensable.

You are co-founders of the ETH Studio Basel, whose urban research has become well known. How did that happen?

The founding of the ETH Studio Basel was a great moment for architecture and urban research. Strong energies came together there. In the beginning there was only the name. For the four architects Roger Diener, Jacques Herzog, Marcel Meili and Pierre de Meuron, one thing was clear: they didn’t want to teach architecture, they wanted to do urban research. And they didn’t want to teach at the Hönggerberg. So, at the invitation of the ETH President, they founded ETH Studio Basel. Before they started, they were looking for a geographer – that’s how I came to Studio Basel.

How did you start your research?

Before the start of the first semester we had no plan, no theory, no methodology. We only had one question: What is urban Switzerland? At the beginning we started from our own personal experiences and examined our own spatial practice. We gave the students a dart and asked them to throw it at a map of Switzerland – and where the dart landed, they then began their investigation. They conducted interviews, took photos, drew maps, discussed. We gradually systematized this process, specifically selected certain locations and gradually developed a process with which we were able to analyze the entire territory of Switzerland.

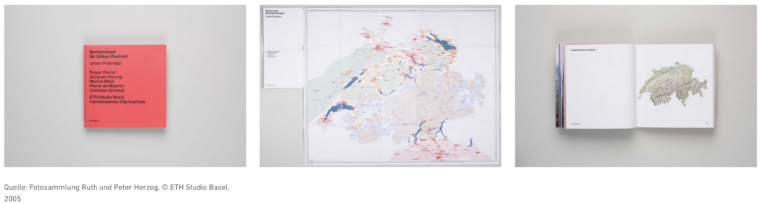

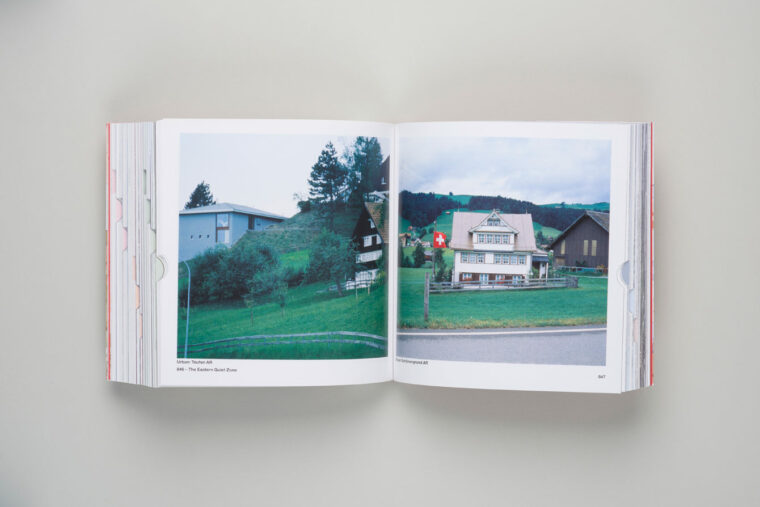

Images of the publication «Switzerland: An Urban Portrait» from 2006

In 2005 “Switzerland. An Urban Portrait” was published. Your research has sparked much discussion. What impact did it have in the long term?

Above all, the publication has changed our perception of Switzerland. We initially omitted the political boundaries because they bring with them prejudices about spacial configurations. We also deliberately ignored the existing spatial planning concepts so as not to remain trapped in outdated representations. And we radically cleared up the ideas of a rural idyll and conveyed a different, urban image of Switzerland. One day the head of the Federal Office for Spatial Development and his senior officials came to Basel for a full day discussion. Our analysis later found its way into the official Swiss Territorial Concept. An entire issue of the weekly supplement of the Tagesanzeiger was also published on the topic. This has contributed greatly to spreading our new image of Switzerland.

The analysis introduced the term “Alpine fallow lands”, which was met with strong criticism in mountain regions. How did you experience that back then?

After our portrait was published, I gave a public talk on our portrait every week for a year – across Switzerland. I could kind of feel the pulse there. There were many exciting discussions. However, the term “Alpine fallow lands” was a provocation. People from the mountain regions were still angry for a long time because of this term, which we actually understood in a positive, active sense – as a call for reflection. However, the fronts then became more hardened. This also had to do with the general political climate. At that time, the “rural” was appropriated by the right-wing conservative SVP, and the contrast between city and countryside was politically reinterpreted. Our analysis has shown that this contrast does not exist in this form in everyday life. Switzerland is more diverse, smaller-scale and much more complex than the simple idea of an “urban-rural divide” allows for. The “countryside” exists primarily as an “idée fixe” in people’s minds. The real world is a different matter.

What do you mean by that specifically?

For example, we compared Valais with Los Angeles. Geographically, these are undoubtedly different places. But people move in space in a very similar way, they are highly mobile and mostly travel in cars. We also pointed out that the “Alpine fallow lands” are heavily subsidized. The term suggests that these areas are waiting for change. Unlike other countries, Switzerland is committed to preserving these places. But we should think about how we want to deal with these areas – and explore alternative development paths. That was difficult to convey.

The Swiss Portrait was published almost 20 years ago. Would it still be so provocative today? Or is urbanized Switzerland firmly anchored in people’s minds?

It is now clear in the collective consciousness that Heidi Switzerland no longer exists – although it is still defiantly celebrated. Due to the strong political polarization, the rural has also lost its idyllic quality. We know that agriculture today no longer has anything to do with picturesque farms, but rather with mechanization, industrialization and interest politics. It has always been like this. But it has never been so obvious, so undisguised. The myths of rurality collide with the realities of pollution, climate change and the dramatic loss of biodiversity. The question is no longer whether we have an urban or rural life. But what form of urbanity we want to have.

Studio Basel’s publications are now published as open access. What do you hope to achieve from this accessibility?

The publications have an important place in architecture and urban research. These are pioneering works. But some books, including the Swiss Portrait, are out of stock. Thanks to Open Access they are available again. Today, publications should also be accessible globally, and not just in a few Western libraries.

Studio Basel closed its doors in 2018. Where does this form of urban research continue in the department today?

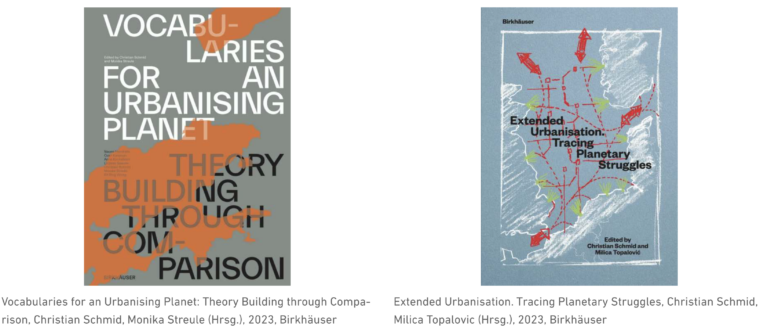

We have further developed this research at the ETH Future Cities Laboratory (FCL) in Singapore and now also in Zurich, among others. Professor Milica Topalović and I have carried out several large research projects in this context. Geographer Neil Brenner, at the time at Harvard GSD, and I developed the concept of planetary urbanization. The term can once again be seen as a provocation and it has triggered controversial reactions. But it gave us a different perspective on the urbanization of the world.

What do you mean by that?

Since the 1980s, urbanization has developed in an encompassing and at the same time incomprehensible way. Today we need a new vocabulary to be able to capture these processes. They can take very different forms and fundamentally transform areas such as the Amazon, the North Sea or Arcadia in the Peloponnese. We examined these urbanization processes on a planetary scale. We no longer distinguish between city and countryside, but between extended and concentrated urbanization.

What does this ultimately mean for architecture?

Architecture and urban planning must address these processes, not only caring for the privileged urban centers, but also for the agglomerations and the peripheries that have been ignored for so long. Good architecture is needed there too. Some municipalities have now noticed this and are increasingly organizing architectural competitions. This change is in full swing, and not just in Switzerland. We also have to take seriously the agricultural areas that we cannot leave to agribusiness. We have to intervene here with concrete architectural and urban design proposals.

Das Original dieses Artikels erschien in den D-ARCH-News am 29.04.2024.