Most cities do not charge for driving. Do you think that is fair? It causes externalities such as noise and pollution to residents and shops. In peak-hours of congestion, valuable life time, money, and fuel are wasted. Do you think driving in the city should be priced? Do you that is fair? This might systematically exclude the poor from the streets. How can we balance these distributional conflicts?

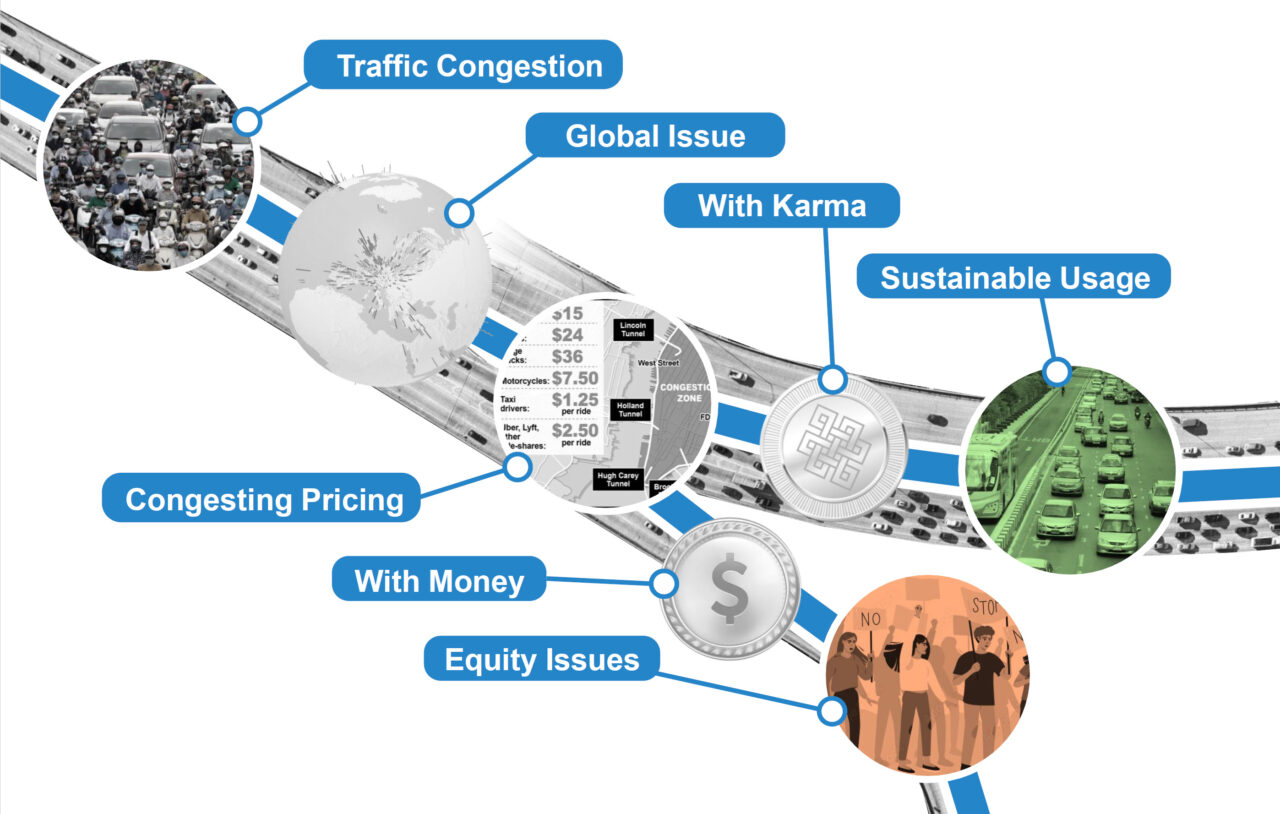

Traffic management systems control demand and supply to reduce congestion. Solutions include the control of infrastructure (e.g. signalized intersections, perimeter control) and of behaviour (e.g. license plate rationing, congestion pricing). While many solutions are well studied and have been proven to work efficiently in practice, few of them reach practical implementation. Major obstacles, especially for economic instruments, include public resistance in the decision-making process and equity concerns.

«Karma is independent of the economic situation of individuals, as it cannot be circumvented with money»

Congestion pricing is a highly controversial topic. The prices to be paid cause an incentive not to drive to the city by car, and instead to carpool, to use public transport, or not to go to the city at all. Despite tremendous efficiency improvements, only a few cities in the world apply this demand management tool. Opponents argue that introducing additional charges will systematically disadvantage economically poorer people from transportation and add additional costs to drivers.

Distributive fairness is concerned with how resources can be distributed to a population of individuals in a fair way. Fairness is challenging to define and usually highly specific to cultural, social, and economic contexts; many different, opposing views suggest different distribution schemes: equality principle, difference principle, greater-good principle, sufficiency principle, equality-of-opportunity principle, and proportion principle.

Artificial currencies such as tradeable credit schemes (TCS) and Karma mechanisms are promising alternatives to monetary incentive schemes to address the equity issues of congestion pricing. TCS are distributed equally across a society, can be sold if not needed and bought if needed urgently by individuals. Karma mechanisms can be considered as non-tradeable credit schemes: the right to drive into the city (e.g. one day) can only be earned by a specific behaviour, which is to not drive into the city (e.g. three days). Karma achieves a balance between giving and taking, and is independent of the economic situation of individuals, as it cannot be circumvented with money.

Kevin Riehl is a doctoral candidate at the Traffic Engineering group (SVT) of the Institute for Transport Planning and Systems (IVT) and the ETH AI Center, ETH Zürich. Before he worked as strategy consultant and software engineer in the Swiss finance & banking industry. His research interests include fairness, computational economics, and traffic control.

Kevin Riehl is a doctoral candidate at the Traffic Engineering group (SVT) of the Institute for Transport Planning and Systems (IVT) and the ETH AI Center, ETH Zürich. Before he worked as strategy consultant and software engineer in the Swiss finance & banking industry. His research interests include fairness, computational economics, and traffic control.