Martina Voser was a Visiting Professor at ETH Zurich from 2021. At the end of 2023, she was appointed Full Professor of Landscape Architecture. She talks about the profound changes that the Swiss landscape is facing and how her chair can develop the necessary transformation processes together with the public sector and experts in the field, .

What does the Swiss landscape need today?

The last three summers alone have shown how much accelerated climate change is affecting water levels in Switzerland: we had either too much or too little water. The drought of 2022 and 2023 has had a lasting impact on our vegetation, and the heavy rain this summer caused devastating mudslides and landslides – and yet this August was, once again, the hottest and driest on record. This unstable hydrological regime will become even more severe in the future, with a chronic deficiency of precipitation and increase in heavy rainfall to be expected. It is also becoming apparent that, due to the increasingly populated landscape, natural events are colliding more and more often with human habitat density. And since water and stone often go in tandem here, the effects in Switzerland are particularly devastating.

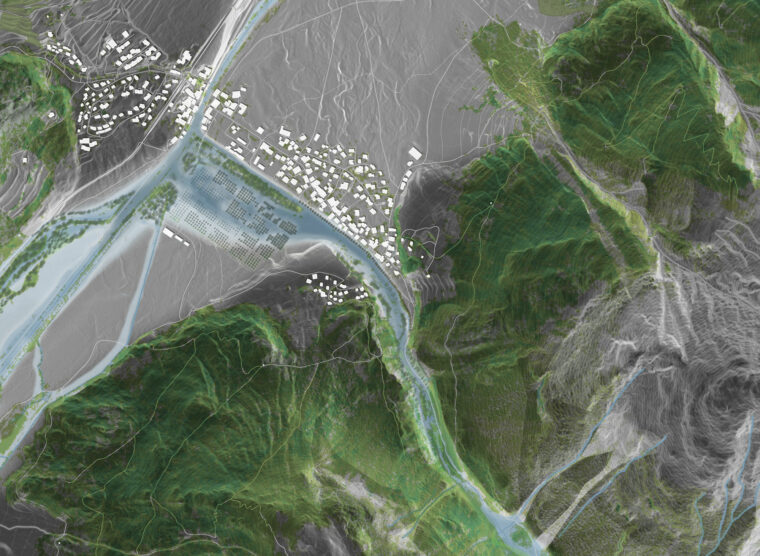

Therefore, from my point of view, we are facing two profound changes; apart from a few Alpine regions such as Valais or Engadine, Switzerland is based on a culture of constant and abundant water supply. The issue here is drainage. To meet the challenges of the future, we need to transition to a culture of erratic and scarce water supply, focusing instead on collection and storage. This implies a paradigm shift – from drainage to irrigation – which causes spatial, structural, and typological changes to the Swiss landscape.

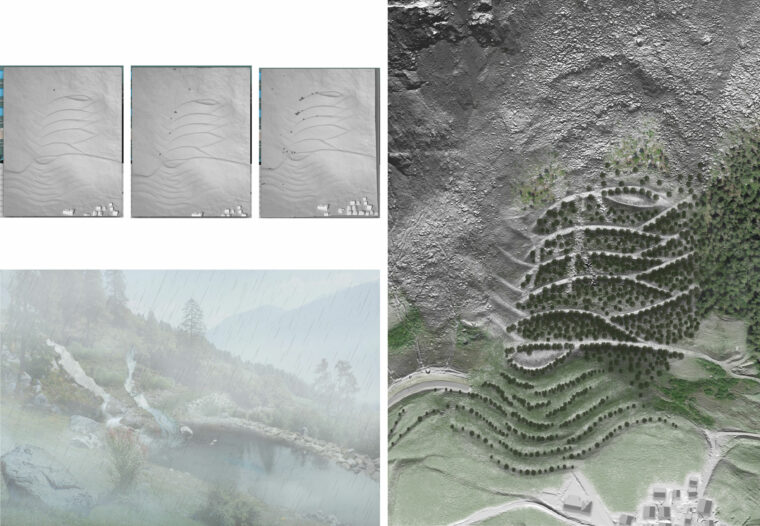

In addition, the increasing amplitudes lead to ever more extreme spatial situations with many new intermediate states and to gradually more extreme erosion and sedimentation processes. This calls for a new approach to natural processes and dynamics. We will have to learn to design spaces with many different intermediate states and temporary uses and to take these processes into account in the design process. Another paradigm shift leads from controlling to directing, from spaces with a single function to multi-coded landscape spaces that ultimately allow for complex coexistence.

Densification represents another challenge: the Swiss landscape has to cope with more and more, whether it is flood protection, the promotion of biodiversity, leisure uses, or building new transport infrastructure. Due to the limited space available in Switzerland, its landscape is under more pressure than anywhere else. Therefore, I am quite convinced that, in the future, we will no longer be able to act in a monofunctional way, but will have to plan and design integral and multi-coded spaces. What we know from urban areas and agglomerations will have to be transposed into the landscape – we need sponge landscapes and integral planning processes for protective infrastructures as well. The project for the protective structures in Bondo, on which our office works, is a good example of the diverse added value that can be generated in this way.

In the search for possible future scenarios regarding this multi-layered cultural paradigm shift, which will lead to profound structural changes – spatial, social, and political ones – in the Swiss landscape, my chair strives for a central role so that credible alternatives can be developed together with the public sector and experts. Together with the work done by our students, we want to search for and design new spaces and images, and develop new typologies on the basis of which we can discuss opportunities and risks. Hopefully, the required adaptation of the landscape can be seen as an opportunity to allow previously unknown spaces and natures to emerge. If we also manage to carry out the adaptation through transformation processes, we are on the right track. I consider this process-based development and adaptation of our landscapes an opportunity. Landscape architects can play an important role in this, because mediation is part of our profession: between scales, between the various specialists, between planners and users, and between history and the future – in order to arrive at solutions as a team and through the actual design process.

Which messages and topics should be disseminated from Switzerland to the world and vice versa?

Due to its size and topography, Switzerland can be seen as a condensed laboratory where many different challenges come together in a very small area. A single catchment area encompasses plains, steep slopes, urban or suburban areas, and heavily rural areas. We also have easy access to data and basic information, and a politically and administratively stable system. This has helped us realize a top-level planning and construction culture, which is often truly exemplary. With regard to the aforementioned adaptation of the planning culture, Switzerland can and must assume a pioneering role. Due to its manageable size and the structures at the political and administrative level, new approaches can be tested, discussed, and consolidated – just as has happened before, when engineers built modern Switzerland. For the adaptation of the Swiss landscape, we can now explore new strategies and types of interdisciplinary co-operation between all actors in spatial research.

Of course, we can learn a lot from other countries, too. With regard to the paradigm shift mentioned before, we should certainly study cultures in arid or monsoon regions. Oases and wadis teach us how flash floods can be used to collect water and how dew can be used for irrigation. Or consider Bangladesh, which is currently being hit hard by the monsoon once again, where schools have floating gardens. Many megacities abroad also show us how we could make better use of rhythms and multi-coding. São Paulo, for example, manages to turn one of the main traffic arteries in the city centre into a place for people to go for a stroll on Sundays.

How can you benefit from the proximity to other NSL chairs?

We can only tackle contemporary challenges together. Integral thinking, holistic action, and networked and interdisciplinary work must become a matter of course. The NSL is the ideal platform for working together across subject areas and departments and beyond the limits of standards and expertise. Therefore, in deciding to locate the chair on the HIL H floor, I consciously sought physical as well as intellectual proximity to the NSL.

Landscape architecture is, per se, a profession based on mediation – we see potential in the in-between. Often, these spaces are not perceived as such, let alone have their own advocates – or they have to accommodate diverging and highly particular interests. As a result, the projects in our office are often caught in the midst of tense arguments between flood protection and cultural heritage or between nature conservation and the pressures of use. Our aim is to translate all these demands into a design of self-evident and high-quality spaces, offering multiple added values for people, flora, and fauna. In turn, these spatial components are reflected back at the cultural and societal level.

Apart from the incredible privilege of now being able to work with and learn from all the experts at the NSL thanks to the professorship, I see the opportunity not only in the self-evident experience of interdisciplinarity. Rather, I am convinced that, together, we can tackle contemporary tasks in a more holistic way and adapt the corresponding planning processes accordingly.

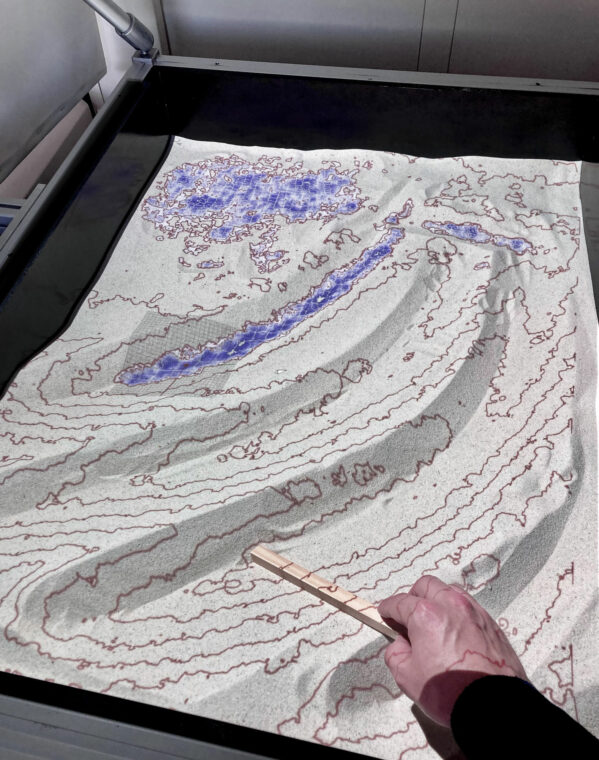

I consider design a wonderful means of finding clever, strategic and, at the same time, specific answers in today’s complex world. At the chair, we also set out to find design methods that incorporate the dimension of time from the very outset in order to be able to control transformation processes that iteratively move back and forth between the digital and the haptic. And we will certainly also be able to benefit from our proximity to the LVML and our colleagues at D-BAUG.

What kind of landscapes do you like to spend time in and why?

There is no such thing as a single landscape; I can indulge my passion for “reading” landscapes in natural, cultural, and urban landscapes. The search for connections, the interpretation of traces and transformations, whether natural or cultural, are a great source of inspiration for me. But don’t worry – alongside all the analyzing, I also like to contemplate things more serenely from time to time…

Perhaps it is fair to say that historical cultural landscapes fascinate me in particular. I am always impressed by the cleverness with which our ancestors interpreted the landscape and worked with natural processes. With the ever-increasing technical possibilities available thanks to industrialization, the subtlety of such interventions has been lost. In the context of contemporary discussions regarding the use of resources, it is certainly not wrong to learn from these old cultural landscapes.

Perhaps I could summarize by saying that I prefer to spend time in places with which I associate stories – whether based on memories or explorations.

Martina Voser, currently owner and member of the Executive Board of mavo Landschaften gmbh and previously Visiting Professor at ETH Zurich, is now Full Professor of Landscape Architecture at the Department of Architecture.

Martina Voser (mavo Landschaften gmbh) is considered one of the most recognized players on the Swiss landscape architecture scene and has received multiple awards for her work. Her projects are not only conceptually sound and visually impressive, but also socially and ecologically motivated. In addition to the outstanding achievements of her practice, she has been a key contributor to professional and theoretical discourse and professional policy for many years. Martina Voser is a committed teacher as well as a sought-after juror, critic, and expert who sits on various commissions and advisory panels