What are the mechanisms at work in the production of territory and what are their effects on the make-up of the human habitat? In order to tackle this question, the research focused on the relationship between forms of collective organization (social, political, and economic) and the forms of territorial organization (the material reality of the man-made environment) by using particular projects in Ethiopia, Brazil, Egypt, India, and Indonesia.

The common thread underlying the case studies, whether in the theoretical or practical trajectories of the work, is the impact of neoliberal models on the production of space. Market-driven development is the prevalent force that shapes both the organization of society and that of territory. Whereas traditional urban discourse maintained a unified vision of the city, present-day discourses must take into account that urban agglomerations are anything but unified. On the contrary, what we encounter today is a fracturing of the social body and of physical space, much in line with what David Harvey identifies as ‹uneven geographical development›.

One of the most upsetting effects of the neoliberal mindset is the increased disparity between rich and poor populations. Whereas development has repeatedly been praised as the solution to overcome poverty, the opposite is the case. Development has nurtured the divide, giving rise to what could be termed ‹development-led poverty›.

Development has been generally lauded as the vehicle for ushering in democratic processes in those regions that are said to lag behind the standards of the ‹civilized› world. However, with a premium placed on economic performance, democracy has been thinned. World-class city scenarios are marketed in city after city, bringing not only glittering skylines but also a blatant erosion of the most basic of rights. Yet some of those most affected by dispossession have become more resilient in countering what amounts to ‹financial apartheid›.

Developmentalist visions are met with other visions of emancipation through grassroots movements struggling to re-constitute citizenship, thereby claiming a voice and a space. And it is with such claims that forms of ‹deep democracy› begin to take root, there where democratic rights have been most tangibly eroded. With insurgencies mounting in the face of inequality, lines of resistance are being drawn into lines of development to alter the course of an exploitative system and assert that the urban poor have a right to urban space.

Researchers of module VI are Prof. Dr. Marc Angélil, Prof. Franz Oswald, Dr. Sascha Roesler, Dr. Cary Siress, Dr. Deane Simpson, Jesse LeCavalier, Dr. Rainer Hehl, Benjamin Stähli, Sascha Delz, Dr. Martha Kolokotroni, Benjamin Leclair-Paquet, Charlotte Malterre Barthes, and Ani Katariina Vihervaara.

Images

1) Aerial view of Cairo’s informal neighbourhoods, Cairo, 2015 for the Shenzhen Biennale 2015 (Charlotte Malterre-Barthes)

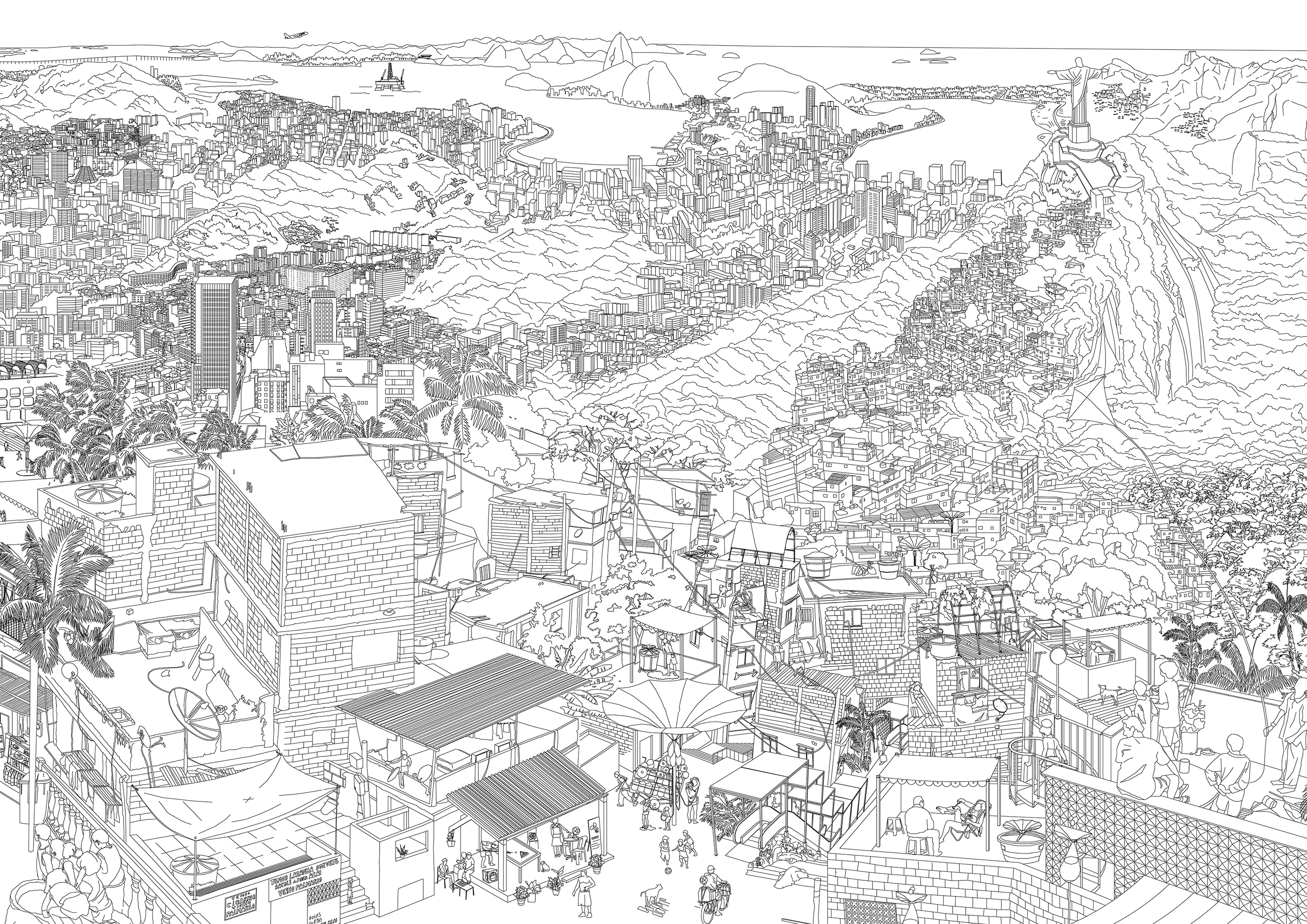

2) Panorama of Rio de Janeiro, ‹Uneven Growth: Tactical Urbanisms for Expanding Megacities›, MoMA, New York, 2014–15 (Rainer Hehl and Something Fantastic)