Doing fieldwork – such as the study of soil, vegetation, or other living systems – is an essential task in the discipline of landscape architecture. It helps to understand and translate the existing conditions of a place to uncover its potential for future transformations. The Chair of Being Alive has organized a one-week residency in the Blenio Valley (Ticino) to learn and experiment with fieldwork methods.

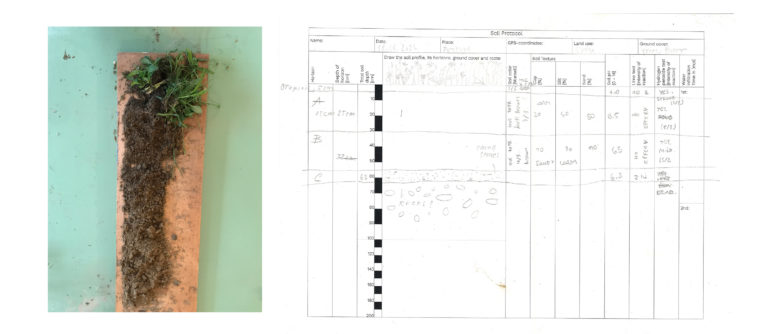

We dug up the soil with garden shovels, spades, augers, and our bare hands. We touched the soil, rubbed it between our thumbs and forefingers, kneaded it, formed it into balls and lines, examined it, smelled it, tasted it, sifted it, ground it, weighed it, and finally dissolved it in sodium oxide. As the week progressed, more and more soil accumulated: A collection of Ziploc bags filled with soil in the corner of the workshop, carefully excavated soil profiles on wooden boards, and piles of excavated soil next to the excavation pits that went unnoticed.

Fieldwork is a very particular approach to getting to know a place. But as a research practice it offers a large repertoire of approaches and tools to explore and study a place in a scientific way. Each fieldwork method is a different lens through which to look at a place; therefore, the understanding changes depending on the technique that is used. The Chair of Being Alive is working on a collection of field research manuals for landscape architects that provide tested and well-documented protocols for carefully studying living systems. The hypothesis of this project is that the methods should be as simple and accessible as possible, without requiring expensive equipment or niche knowledge.

During the one-week residency, three different techniques for soil analysis yielded very different types of knowledge. Taking soil samples with a soil auger revealed not only the depth of the soil and its roots, but also physical and chemical information such as texture, pH or soil color. Soil chromatography vividly shows soil-life interactions such as the presence of organic matter, nutrients, and enzyme activity, and allows conclusions to be drawn about soil health. The underwear test is a simple method for examining biological activity in soil. By burying pieces of cotton in the soil for two months, soil organisms such as fungi and fauna break down the cotton and indicate their activity. Results of diverse simple soil testing methods can complement or contradict each other. Their individual qualitative conclusions must be balanced and nuanced between each other, but, even so, they help us to understand and capture the complexity of the soil.

In the task of understanding Cima Città, we looked at its soil. We decided which were the elements we wanted to document, the methods at our hand for that purpose, and the process of rearranging those scattered insights. This resulted in our personal translation of the place, that we can share with others, too.

Stefan Breit, Uxia Varela and Insa Streit research and teach at the Chair of Being Alive at ETH Zurich. They co-organized the fieldwork week at Cima Città, an interdisciplinary residency space in an old chocolate factory in the Blenio Valley / Ticino.