Marc Angélil’s stance for multidisciplinarity influenced the research of his chair, his message to the students, and his award-winning publications. After more than two decades at the ETH Zurich and thus at the NSL, he will be emeritus. Sascha Delz interviewed the searcher for the essence of urbanism about the underrepresentation of economy at the NSL, the mechanisms at work in the production of territory, global perspectives of urbanisation processes, and his political advice for students.

You are the only architecture and design chair currently affiliated with the NSL. Why did you join the NSL?

The Network City and Landscape was at the time when it was founded the only research platform at ETH Zurich addressing what I would call environment-making practices at the large scale. In this respect, it was important to have the discipline of architecture, which normally focusses on buildings, be involved in debates on how to shape the environment as a form of architecture in the future: not only the city as architecture, but also the territory (landscape and infrastructure included) as a form of architecture.

What were the most important benefits and challenges over the years?

Both the benefits and challenges are framed by the multidisciplinary nature of the NSL, which we tried to use to our advantage by initiating a series of collaborative research undertakings. These projects allowed us to overcome disciplinary boundaries by bringing a number of fields together (sociology, architecture, landscape architecture, transportation systems, infrastructure and territorial planning), all working on common research questions. This is to acknowledge that the various disciplines are co-responsible in the production of the socio-spatial environments that we collectively inhabit.

What would you recommend for the NSL’s future?

First, the NSL must identify its blind spots if it truly wants to remain at the forefront of academic research. To give you an example, the field of economy is undoubtedly underrepresented within the current NSL framework, though we all know that urbanization is fundamentally tied to capital flows. Second, greater attention must be given to the transfer of research findings into practice. The latter must include policy-making, which brings us to the question addressed by the current newsletter – namely, the role of politics and governance in the production of space.

Your own research and writing addresses what you refer to as the political economy of urban and territorial form. What is your understanding of this term?

We are interested in investigating the mechanisms at work in the production of territory. The forces acting upon and thus forming the spaces that we inhabit are certainly economic in nature and insofar politically driven as they pertain to the formation of a collectively inhabited environment – thus our emphasis on what we call the political economy of environment-making practices.

Your chair’s research conducted over the past decades has addressed a variety of contexts and topics, whether in Africa, Latin America, Asia, or here in Europe. Is investigating the political economy of urban and territorial form what one could see as a red thread? And, are there any other specific or repeating commonalities with regards to topics or methods?

In terms of method, the first step for us has always been observation – i.e., describing what one sees on the ground, in a specific location and within a given culture, in order to then, in a subsequent step, investigate the particular economic and political frameworks that have contributed to the formation of particular socio-spatial constellations. A further phase of the work aims to identify the theoretical models (or epistemological frameworks) produced by a given culture addressing the relation between thinking and particular forms of making. With this in hand, we generally move to a more proactive mode of research, framing a critique of the status quo and ultimately proposing alternatives via design propositions, which include not only the design of physical space, but also the design of policy strategies.

In your opinion, what are the most important – or surprising – aspects that your chair’s research projects have contributed to the field of architectural and urban research?

Whereas traditional urban design has always aimed to establish a particular form of order, our research has foregrounded the unevenness of the forces at work in territorial production, both socially and physically. Uneven development is at the core of contemporary environment-making and cannot only be seen as some side effect of particular practices. On the contrary, uneven development must be understood as a primary principle of today’s political economy of space – the entropic condition of the physical realm and abandoned territories, not to mention urban and rural poverty, the marginalization of populations, enclaves of wealth, and so forth.

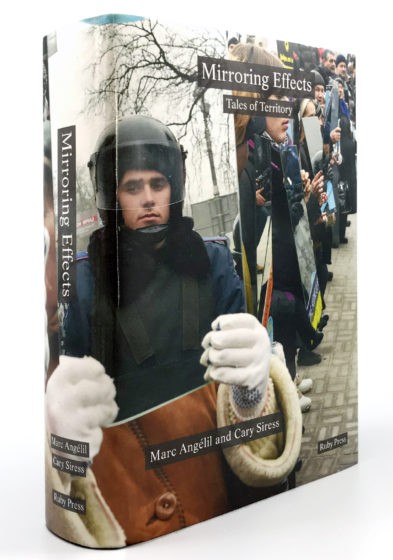

Your latest publication Mirroring Effects: Tales of Territory (co-authored with Cary Siress) offers intriguing and critical insights into a global web of contemporary urbanization processes. In your opinion: Why is it important to address global perspectives as an architect and researcher?

Whatever we do today must be seen from a twofold perspective – namely, from the vantage point of the specificity of a local condition as well as from the vantage point of shared global circumstances. The latter might pertain to the transformation of the world environment in ecological terms and/or to the role of integrated world capitalism, which undoubtedly entangles any locality in a broader field of tension. Accordingly, our book oscillates between the socio-spatial particularities of a place somewhere on the globe and its relation to global forces at work. In order to make what might appear abstract more tangible, we decided to use the format of storytelling as a technique to communicate our thoughts. The tales describe what is going on in situ at the intersection of the local and the global. In so doing, the tales reflect on potential alternatives and forms of resistance to the powers that be. These are tales with footnotes. They not only chart the course of capital-led development in settings as diverse as Addis Ababa, Mumbai, Cairo, São Paulo, Berlin, Paris, and Shanghai. They also offer glimpses of where our geo-economic order might be heading, for better or worse, given prevalent modes of global environment-making practices. The stories told, if casually overhead, could just as easily be misconstrued as the stuff of incredible fables. Yet, they are nonetheless real.

Referring to the book’s title, how do you critically reflect your own role and context within this process?

The book is politically motivated. It offers a kind of mirror to the human condition. More than simply a metaphor, the mirror is used as a trope to highlight what is going on. Our condition is reflected in the mirror, which in turn entices us to reflect upon our own collective actions: De te fabula narratur (of you – or better, of us – the story is told)!

Apart from your research efforts, you have also been a dedicated, life-long teacher of design and architecture. How have your teaching and research activities influenced each other?

In contrast to other colleagues, I am not necessarily promoting an amalgamation of teaching and research. I would like to argue that one should generally distinguish among various forms of teaching, be it the design studio, the seminar, or the work with doctoral candidates. The various formats have different pedagogic objectives, each requiring fundamentally different approaches. Whereas the design studios, in my case, primarily focus on the design of processes concerning the production of socio-spatial urban constellations within a particular culture and place, the work at the doctoral level is more closely associated with particular research investigations. The seminars, on the other hand, offer the students a platform to engage in debates on yet unresolved issues – in our case, the role of advanced capitalism in territorial production and its effects on the environment.

How has this determined your view on the profession of architecture?

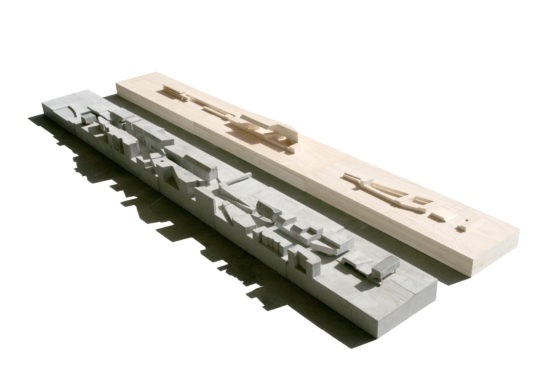

Though I tend to keep professional practice and my work at the academy apart, they both mutually reinforce each other. Take for example the interest in the office or atelier – at agps architecture – in questions of political ecology in the making of socio-spatial environments. The urban ensembles and buildings that we design always address their potential effects on society and the environment. Additionally, we have over the years become more politically engaged. In this sense, connections have been established between the university and practice.

What are the main aspects that you would like to hand on to the new generation of architects?

Become politically active as a collective of engaged citizens!

This interview was made by Sascha Delz, who holds a Doctor of Sciences and a Master degree in Architecture from ETH Zurich. He is currently a postdoc researcher at the Institute for Urban Design of ETH Zurich.

Marc M. Angélil has been a Full Professor for Architecture and Design at ETH Zurich, Department of Architecture since April 1997 and will be emeritus by the end of July 2019. His office agps architecture is a design team with studios in Zurich and Los Angeles, bridging the domains of urban design, infrastructure, landscape, and architecture.