It is widely assumed that popular visual art, such as murals, can potentially be a powerful driver for urban regeneration with important social, economic and environmental benefits. The voices of those directly affected by these type of interventions, however, are often missing. Our research in two informal neighbourhoods in Bogota focused on residents’ perceptions of Habitarte, a government-led programme in informal settlements.

With pressure to present tangible results, governments are often drawn to the «lighter, quicker, cheaper» approach of creative placemaking that seemingly lower the stakes of possible negative impacts. However, ignoring the unintended consequences of imprinting a homogenizing image and very particular aesthetics across impoverished informal settlements seems to be a perilous strategy in particular when only lip-service is paid to the importance of community participation.

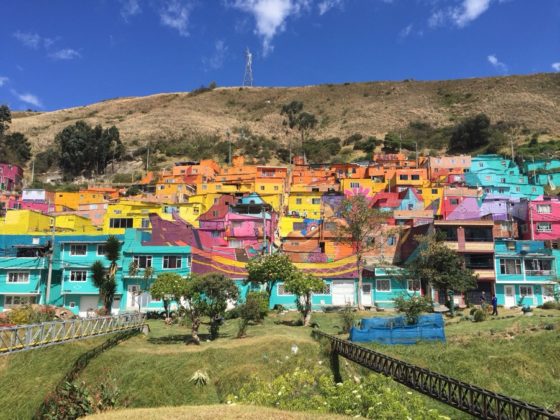

Habitarte is by far the largest urban art-based upgrading programme ever carried out in Bogota. Implemented in 83 neighbourhoods the programme takes place through two kinds of interventions. In the first case, small scale murals are carried out by artists in strategic and often neglected public spaces through an alleged process of co-creation; in the second case inhabitants agree on a macro-mural that covers the whole neighbourhood and can be seen from afar. The programme so far resulted in the painting of 95.000 facades, 141 murals and four macro-murals.

Inhabitants prefer smaller scale murals carried out by local artists

In January 2019 we conducted fieldwork in two informal settlements in Bogota. Over 70 in-depth interviews with women and men revealed that the project did not succeed in overcoming community’s mistrust in government, whose motives were questioned by a large number of interviewees. Residents repeatedly voiced their fears and concerns of what might be the real objectives of the programme, such as eviction and increase in taxes. Additionally, although the programme explicitly aimed to demarginalize and destigmatize informal settlements, many residents felt that the government’s intention was to visually mark poor and dangerous neighbourhoods. Furthermore, many people resented the strong colours used by the programme to paint the facades of their houses, which they considered ‘excessively folkloric’ or ‘lacking elegance’. These widely diffused dissatisfactions and fears highlight the risks of participatory processes limited in scope, participants and time, that finally jeopardize projects’ initial objectives.

In contrast, there was a general appreciation of smaller scale murals carried out by local artists employed by Habitarte. In this case, themes and colours were decided in consultation with local communities and were not only able to transform public spaces, but also to improve the residents’ perceptions of local artists. Hence, elements of the project that were done by and with the community were perceived positively and strengthened relationships between different local actors. This confirms the seemingly obvious, yet often ignored answer to the question of who should be doing the making in placemaking?

Dr. Jennifer Duyne Barenstein is a social anthropologist specialized in socio-economic and cultural aspects of housing, infrastructure, urban development and participatory research methods. She has over two decades of international academic and professional experience in participatory research. Her PhD focused on collective action in water management in Bangladesh and aimed at the development of participatory management policies for flood control, drainage and irrigation systems.

Daniela Sanjinés is an architect, urban planner and researcher interested in the challenges of rapid urbanisation, inequality, and spatial exclusion seen through the lens of housing. As a researcher at the ETH Wohnforum, she teaches at the MAS ETH in Housing and is currently engaged in research projects in Switzerland and Latin America.

This project was conducted in partnership with the Universidad de los Andes in the framework of a seed money grant from the Leading House for Latin American research of the University of St. Gallen.